Dan Foley’s no stranger to challenging retrofits. The one at hand wasn’t terribly unusual, but it required an educated eye to see what was ailing the facility.

Hint: At startup, the hydronic system’s ∆T was a mere 120 degrees.

Foley, president and owner of Lorton, Va.-Foley Mechanical, Inc. earned his doctorate in hydronics (oh, I jest) through his 34 years of jobsite experience while installing, servicing, repairing and replacing hydronic and HVAC systems large and small.

Along the way to achieving mechanical stardom, Foley received a Bachelor of Science Degree in business management from Virginia Tech in 1988.

Foley’s professional trajectory has been on an upward tilt for decades, but he admits there were plenty of frustrations and hard knocks along the way. But to offer insight into his incredible success, there’s no better way than going … back to the future.

“I learned real fast that I had no hope of professional satisfaction if I was to sit behind a desk,” he told me way back in 1988 when we first met. Then a new industry writer, I quickly acquired an appreciation of hydronic systems; after all – I had guys like Dan Foley, Dan Holohan and John Barba to educate and entertain me along the way.

When Foley spoke those words, he was helping a new technician understand the concept of “circulation strategy” while supervising the new guy’s work. The emblem on their shirts identified their employer: Arlington Heating & Air Conditioning, a company that’s since become a friendly competitor of Foley’s own enterprise. At the time, Foley was an installer; he left the firm in 2002 to launch FMI – Foley Mechanical Inc.

Impressive yet down-to-earth

For many years, Foley served on local and national boards of the Air Conditioning Contractors of America. Today, he serves on the board of Virginia’s Plumbing Heating Cooling Contractors Association and is a past president of the RPA. Also, Foley holds master HVAC and master plumbing/gas fitting licenses in Virginia, D.C., and Maryland. He’s shared his knowledge with a monthly column he used to contribute to PHC News and most recently currently hosts a podcast with PHC News Editor Steve Smith.

For anyone new to the field, those are impressive credentials.

But if you know Dan you’d know him as an engaging, down-to-earth guy with a humble personality.

Every couple of years I make a pilgrimage to the D.C. metro area where FMI now reigns supreme. Foley’s jobs – often unique in their complexity and design, whether new or retrofit – are an irresistible draw.

But, I digress. We were just about to take a closer look at a commercial hydronic system, weren’t we? The one with the 120-degree ∆T.

Meade Street challenge

To do that, we’ll move the clock to the early fall of 2016. Deep in a mechanical space, surrounded by the complex piping network that serves a commercial hydronic system, Foley made an intelligent survey of the system at a 30-unit condo building in Arlington, Va., (a second building in the condo development, with 26 units, is the first building’s a near-twin; it now has a similar FMI-installed hydronic system). The buildings there were constructed as apartment structures shortly after WWII; the living units range from 675-900 square feet.

The location is the envy of the D.C. area, offering residents a brief walk across the Key Bridge into Georgetown.

Mike Myers, president of the condo development’s board of directors (and also a condo owner there), was confident that Foley could help sort out some issues they were having with the heating system.

For Myers, the challenge they faced was personal. Not only had he lived in the building, he’d taken it upon himself on one brutally cold evening to keep residents warm.

Myers recalled sitting in a chair all night down in the boiler room, accompanied only by a radio. He learned that the apartment building’s big, cast-iron boiler’s igniter was faulty. So he spent the entire night pushing the reset button when the system shut off.

During Foley’s first visit there, he asked questions of the facility manager, a man who was clearly impressed with Foley’s insight and proficiency. Foley took photos, making note of a cracked cast-iron boiler sections “stacked like cordwood.” Foley also made measurements, filling pages with notes and schematics.

A solution

Within an hour, he’d arrived at a solution, with final notations about the materials and equipment he’d likely need to restore health to the ailing mechanical system.

When Foley first surveyed the system, the weather was mild. Yet the cast-iron, forced-draft boiler was firing away, full-tilt. It wasn’t long before Foley found water seeping from a boiler section. He was informed that, over the past few years, many cracked sections had been replaced – explaining the pile of cast-iron sections.

Making matters worse, the section now leaking had been replaced just a few months earlier.

“The [facility’s] board was sick and tired of paying for repairs and high gas bills while dealing routinely with no-heat challenges,” Foley says. Residents were regularly complaining of discomfort: “We’re too hot,” or “We’ve got no heat” were common protests.

During his survey of the facility and mechanical systems, Foley saw many open windows with temperatures in the living units close to 80 degrees.

No wonder the gas bills were so high: The heating system consumed 47,017 cubic feet of gas before the retrofit.

The existing boiler was from a reputable manufacturer, so it was unlikely that defective castings were the cause of cracked sections.

When Foley dug into the control strategy, he was rewarded with an “aha!” moment. System pumps were controlled by an outdoor thermostat set to 60 degrees. When ambient temps dropped below that, the pumps kicked on to circulate hot water to radiators and heat emitters.

Foley discovered that the boiler was turned on in the fall with the burner controlled by the high limit; clearly a hurried, jumped-out fix some years ago. Maybe the service tech intended to return to re-enable a T-stat. Or, perhaps the tech even planned to install outdoor reset controls to bring some intelligence to the operation.

Apparently, however, it never happened.

The boiler – responsible for all radiator space heating within the building had a steady temp of 180 degrees, spring, fall, or midwinter (that is, if the boiler wasn’t leaking all over the boiler room floor). Not only was this control setup extremely wasteful and inefficient, it was surely the silent killer of cast-iron boiler sections.

When system circulators activated at start-up, the flow of cold, return water hitting the 180-degree cast-iron sections created a perfect storm within them; the thermal shock was more than they could withstand, causing them to crack and fail.

Foley found that domestic hot water was provided by a two-plus-decades-old copper fin tube boiler paired with a storage tank. The DHW system was piped and controlled properly, but required constant maintenance and repair, and suffered from regular breakdowns. A few times a year, it was sure to leave the 30 living units in one building or 26 units in the other with no hot water.

Comfortable, reliable and efficient

Foley’s goal: to present a solution that was comfortable, reliable and efficient, and in that order. (See sidebar for more on this approach.)

He presented his plan to the facility’s board of directors, yet some members didn’t agree with Foley’s solution, complaining that they didn’t have the funds for a full-system solution.

Foley’s reply: “How’s that approach working so far? You’re paying for this whether you want to or not. Currently, you’re paying for repairs and emergency service, and unnecessarily high gas bills. And you’re paying through tenant unhappiness through the no-heat calls. And, there are the no-hot-water problems to address as well. Why not direct your funds toward a long-term fix?”

At last, the board approved Foley’s proposal. Soon, FMI crews, with Brian Golden tapped as the project supervisor, were unloading gear from trucks. As the fall of 2016 brought colder weather, Foley crews demo’d the cast-iron boiler as heat wasn’t needed at the time. They also removed the near-boiler piping, circulators and controls. They left the DHW system intact, temporarily.

Foley chose four mod-con gas boilers to meet the need for space heating of the total of 56 dwelling units and common areas in both buildings. He’d chosen – for each facility –two mod-con boilers to provide redundancy as well as to handle low-load heat demands without short-cycling. Near-boiler piping and system components were replaced, including the installation of three new, heavy-duty, three-piece Taco Series 1600 in-line pumps, each coupled with Taco triple-duty check valves.

For the chilled water systems, the trump card, however, came in the form of two Taco base-mounted, self-sensing pumps.

“Taco’s self-sensing technology offers an integrated pump and drive. For each building, we installed two for full redundancy,” Foley says. “They’re set up in a lead-lag configuration, each capable of providing full system circulation. So if there’s a call for 60 gallons a minute in the middle of the night, and one falters, the other merely assumes control.

Self-sensing pump performance curves are embedded in the speed controller’s memory. During operation, pump power and speed are monitored, enabling the controller to establish the hydraulic performance and position in the pump’s head-flow characteristic. This enables the pump to continuously identify required head and flow at any point, providing accurate pressure control without the need for external sensor feedback.

“The self-sensing pumps replaced a large, single-speed pump with a manually-operated starter,” Foley explains. “They were needed as the system overhaul’s centerpiece. The supply and return piping was rotten; there was condensate leakage. It was a real mess. The board’s decision – this time, for the first time – wasn’t based on price. They opted for reliability and performance.”

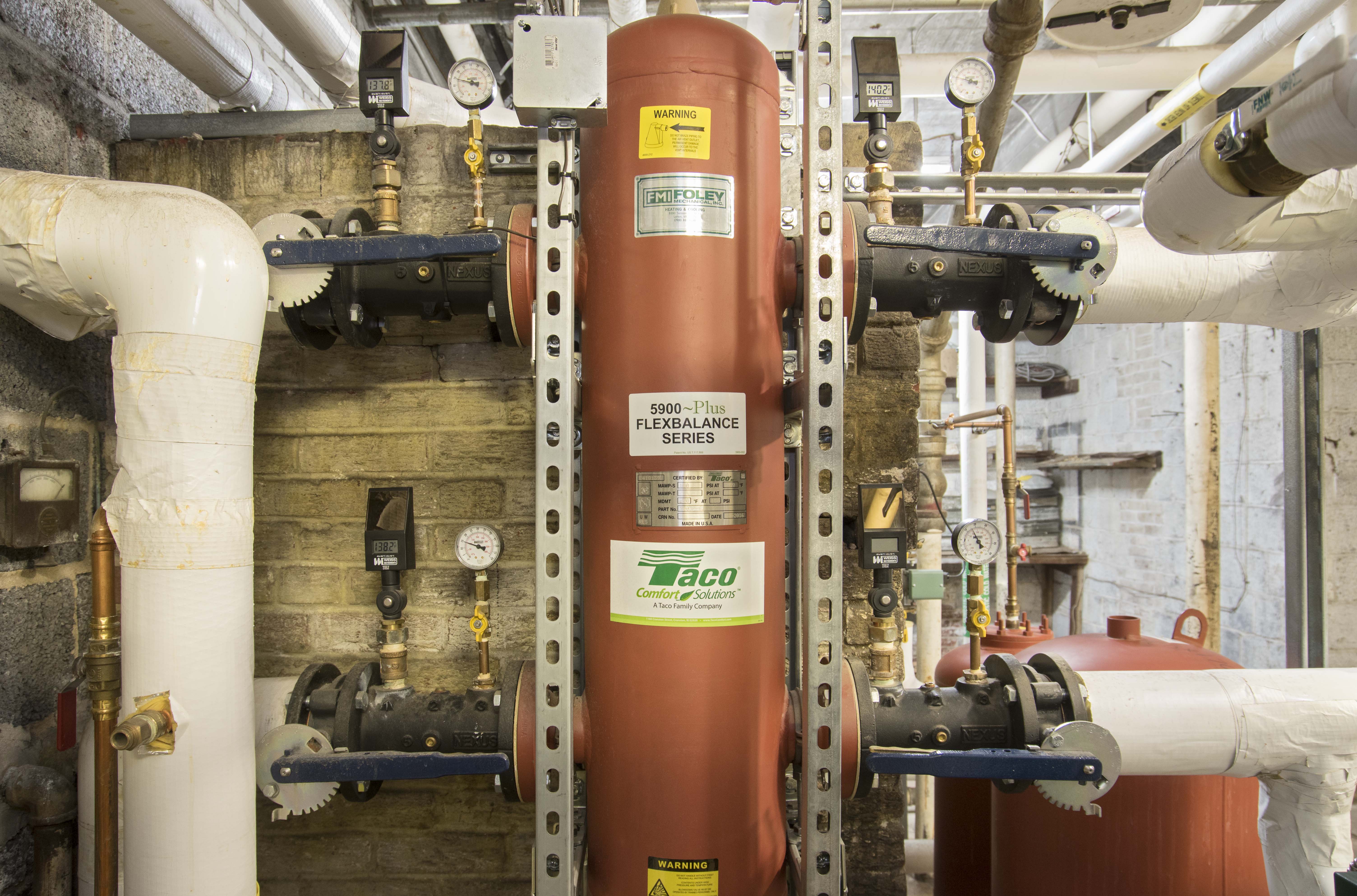

Foley pros also installed three heavy-duty, ASME-rated Taco expansion tanks, one each for the hydronic side, chilled water, and one for DHW. Also, two of Taco’s 1600-series pumps, with pump starters, serve the hydronic heating system; a Taco 120 Series pump serves the DHW. Foley also chose a Taco four-inch 4900 Series hydro-separator to serve the hydronic system, balancing boiler and system flow.

Today, the new boilers provide the building’s DHW through a commercial indirect tank, set as priority. Foley also replaced a broken domestic recirculation pump – installing a Taco 008 stainless steel SmartPlus recirc. All of the exposed piping was insulated with fiberglass pipe insulation and identified with pipe markers.

FMI was ready to fire-up the system just as a new winter season swept in. Technicians programmed the controls to activate system heat when outdoor temperature dropped below 58 degrees. Outdoor reset control adjusted supply temps to match building heat loss, ensuring resident comfort.

After initial tuning, the system worked flawlessly to provide even heat and limitless DHW. The board decided to have Foley’s team install an identical system in the adjacent building over the following months – which then led additional work nearby.

Since that time – now, six years later – system reliability at all of the buildings has improved 100 percent. Comfort levels were dialed-in, the reset control negating the need for residents to adjust temps by opening windows

Foley knew that facility managers would see a decrease in fuel use, but he could only guess at the savings.

Luckily, Myers and another board member compiled fuel usage data for two years before and after the upgrade and – surprised by the results – they continued to compile data. What they discovered was rather startling: the previous heating system consumed 47,017 cubic feet of gas in the two six-month cold-weather periods before installation of the new systems, and 28,729 cubic feet of gas in two cold-weather periods immediately following installation of the new systems – for a total savings of almost 40 percent.

At that rate, and with the new system’s completion of its seventh winter season, the facility’s board of directors estimates that they’ve already fully recovered their investment on Foley’s heating system retrofit.

“Getting rid of the over-sized cast-iron boiler was a first step in the right direction,” Myers adds. “That thing was big enough to sleep in. Today, none of the condo’s board of directors regrets the decision to replace the system. Foley and his crews really came through for us. We’re all very impressed with their work, and the results.”

“It’s a recipe that’s worked, and worked well,” he concluded.